A Probabilistic Analysis of Distance Metrics on Grids

I've wondered for a while why streets are organized in square grid-like patterns almost ubiquitously. Occasionally, there might be a street running diagonally or there might be some ill-placed monument requiring a roundabout, but the default rules of city planning seem to be:

-

Intersect streets at a right angle

-

Keep the distance between intersections uniform

Of course, I know nothing about city planning so forgive my ignorance. If I was a guessing man, I'd venture that square-like grids exist for good reason. For one, they facilitate our addiction to other rectangular objects, like buildings. They also are remarkably simple to navigate. To get from any one point to another on a rectangular grid, it takes at most 1 turn. But ignoring these concerns, is there a way to mathematically quantify their optimality?

Suppose I am a blob on a grid of some kind. I want to travel a euclidean distance of 1 mile (or kilometer depending on your creed) away in some random direction, but I'm only allowed to use the streets of my grid. How far can I expect to walk?

Formally, suppose we sample a direction $\mathbf{\theta} \sim U(0, 2\pi)$ uniformly at random. Then, if $\vec{p} \in \R^2$ is our current position, $\mathbf{\vec{q}} = \vec{p} + \begin{bmatrix} \sin(\theta) & \cos(\theta) \end{bmatrix}^\top$ is a random point 1 unit away. The shortest distance between $\vec{p}$ and $\mathbf{\vec{q}}$ if we only traverse the "streets" of our grid is given by $D(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}})$. We wish to understand the distribution of $D(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}})$ and perhaps most important, compute $\mathbb E[D(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}})]$, the expected distance.

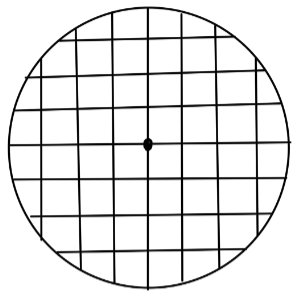

Square Grid

We start with the case that motivated this whole thought experiment, and, as it turns out, the easiest to solve.

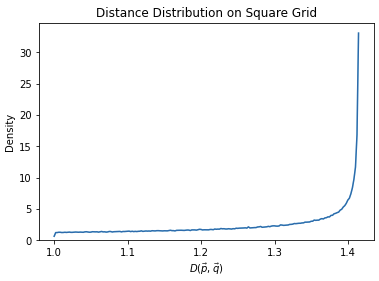

In the figure above, many points along the circle don't intersect with the grid. This problem is solved by considering an arbitrarily small grid, such that any point on the circle is within $\epsilon$ of a point on the grid. Then the distance metric on this space is given by the $\ell_1$ norm, also known as the manhattan distance. \[ D_s(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}}) = \|\mathbf{\vec{q}} - \vec{p}\|_1 = |\sin(\theta)| + |\cos(\theta)| \] This isn't a distribution that has a clean pdf, but we can generate samples of $\theta$ because it's a simple uniform distribution and transform those. Then, to avoid the clunkiness of dealing with histograms, we can use Gaussian Kernel Density estimation to estimate a continuous pdf.

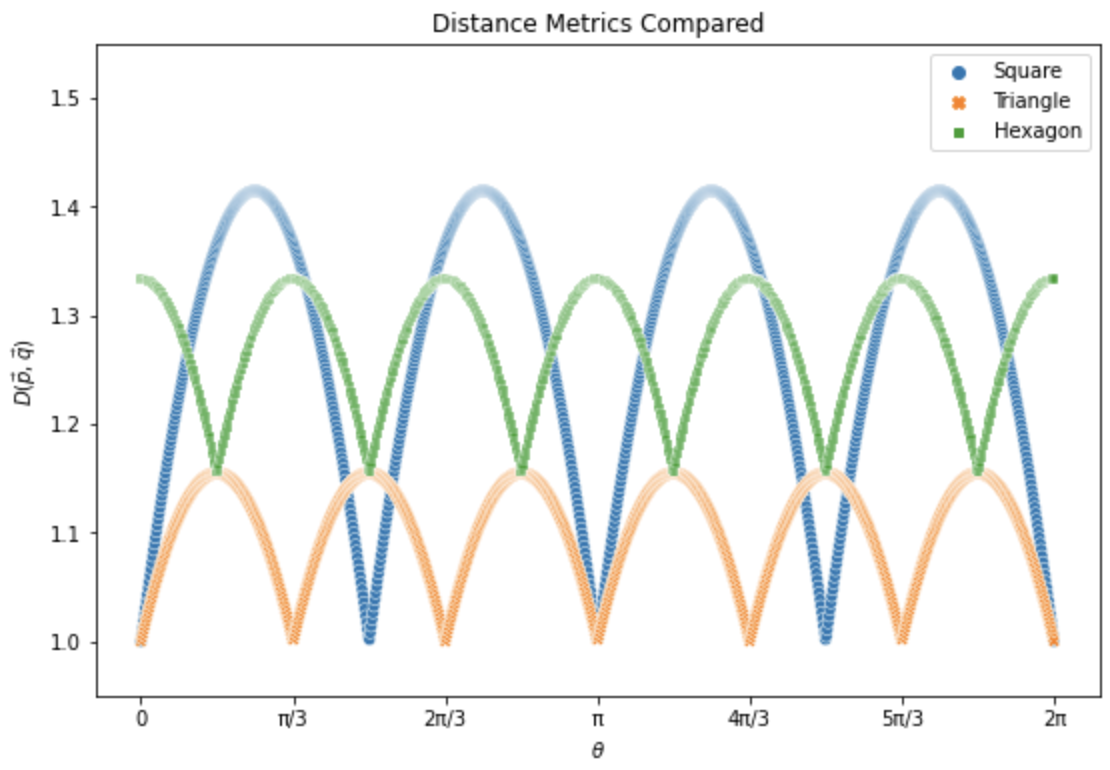

Some quick facts about this distribution. First, the best case distance (minimum) is 1 when $\theta = z\pi/2$ for any integer $z$. The worst case distance (maximum) is $\sqrt{2}$ when $\theta = (2z+1)\pi/4$. Now's we compute the expected distance. \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb E[D_s(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}})] &= \int_{\Omega} D_s(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}})p_\theta(t) ~ dt \\ &= \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} |\sin(t)| + |\cos(t)| ~ dt \end{aligned}\] Computing this integral might seem annoying until we notice that the distance function is symmetric across all 4 quadrants. In the first quadrant (when $0 \leq t \leq \pi/2$) $\sin(t) \geq 0$ and $\cos(t) \geq 0$, so we can get rid of the absolute values and solve the integral with basic tools. \[\begin{aligned} \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} |\sin(t)| + |\cos(t)| ~ dt &= \frac{2}{\pi} \int_{0}^{\pi/2} \sin(t) + \cos(t) ~ dt \\ &= \frac{4}{\pi} \\ &\approx 1.273 \end{aligned}\] The simplicity of this solution is quite satisfying.

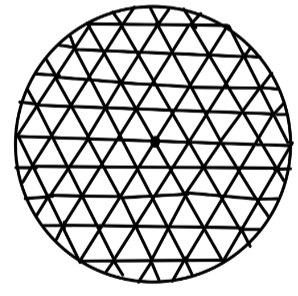

Triangular Grid

Now, suppose our grid was tiled with equilateral triangles, as in my artistic reproduction below.

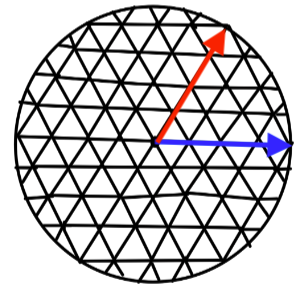

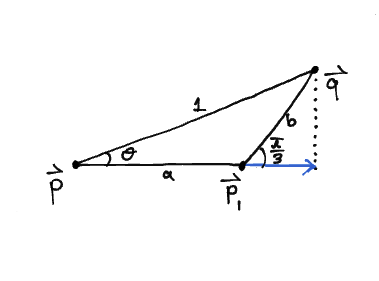

One observation which will make the rest of our derivations easier is that every "sextant" (or $\pi/3$ slice of the circle) is symmetric. Specifically, $D_t(\vec{p}, \vec{q}_1) = D_t(\vec{p}, \vec{q}_2)$ if $\vec{q}_1 - \vec{p}$ and $\vec{q}_2 - \vec{p}$ are $\pi/3$ rotations of one another. See the vectors represented by the blue and red arrow below for reference.

Looking at the sextant between the blue and red arrows, any point $\vec{q}$ lying on the unit circle on this sextant can be reached by first traversing along the blue arrow from $\vec{p}$ to a point $\vec{p}_1$ where the angle between the vector $\vec{q} - \vec{p}_1$ and the blue arrow is $\pi/3$. Then, by traversing in the direction of the red arrow until the point $\vec{q}$. This is hopefully made more clear with the drawing below.

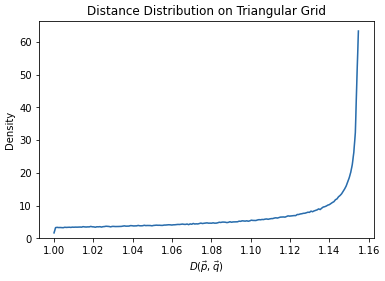

Given some $\theta \in (0, \pi/3)$, $D_t(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}}) = a(\theta) + b(\theta)$, where $a$ and $b$ are the side lengths of the triangle above. For $\theta$ outside this range, we can make use of symmetry defined earlier. We compute $a(\theta)$ and $b(\theta)$ with a formula I thought I'd never see again, the sine law: \[ a(\theta) = \frac{2\sin(\frac{\pi}{3} - \theta)}{\sqrt{3}}, \quad b(\theta) = \frac{2\sin(\theta)}{\sqrt{3}} \] Now, we can once again sample the distribution of $D_t(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}})$:

This has a very similar distribution to the square grid with perhaps a heavier left tail. The best case (minimum) distance is 1 obtained when $\theta = z\pi/3$ for any integer $z$ and the worst case (maximum) distance is $\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}$ when $\theta = (2z+1)\pi/6$. The derivation for the average case is similar to that for the square grid: \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb E[D_t(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}})] &= \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} D_t(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}}) ~ dt \\ &= \frac{3}{\pi} \int_{0}^{\pi/3} D_t(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}}) ~ dt \\ &= \frac{3}{\pi} \int_{0}^{\pi/3} \frac{2\sin(\frac{\pi}{3} - t)}{\sqrt{3}} + \frac{2\sin(t)}{\sqrt{3}} ~ dt\\ &= \frac{2\sqrt{3}}{\pi} \\ &\approx 1.103 \end{aligned}\] This is a significant improvement on the expected distance with a squared grid. To put it into perspective, if I was travelling at a constant speed from $\vec{p}$ to $\vec{q}$, I'd expect to take about 10% longer by following a triangular grid than by following no grid at all, and about 27% longer by following a square grid.

Hexagonal Grid

We now evaluate our last regular polygonal grid (triangles, squares, and hexagons are the only regular polygons that tile a plane).

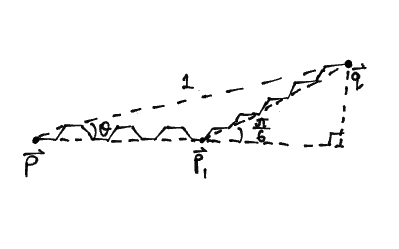

One can construct the hexagonal grid by removing edges from the triangular grid, so as it turns out the analysis for our distance metric on the hexagonal grid is quite similar. First, you can show that every (1/12)-th slice of the circle is symmetric on the hexagonal grid. As a result, we will only evaluate the distance metric on the circular arc between the points $\vec{q}_1 = \vec{p} + \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}^\top$ and $\vec{q}_2 = \vec{p} + \begin{bmatrix} \sqrt{3}/2 & 1/2 \end{bmatrix}^\top$, which is the set of points that satisfy $\theta \in (0, \pi/6)$. In this section of the circle, it can be shown that the shortest path between $\vec{p}$ and $\vec{q}$ can be chosen to satisfy the diagram below:

Hence, we can write: \[ D_h(\vec{p}, \vec{q}) = D_h(\vec{p}, \vec{p}_1) + D_h(\vec{p}_1, \vec{q}) \] When the hexagonal grid is dense, \[ D_h(\vec{p}, \vec{p}_1) = \frac{4}{3}\|\vec{p}_1 - \vec{p}\|_2 \] and \[ D_h(\vec{p}_1, \vec{q}) = \frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}\|\vec{q} - \vec{p}_1\|_2 \] The values $\|\vec{p}_1 - \vec{p}\|_2$ and $\|\vec{q} - \vec{p}_1\|_2$ are found by applying the sine law to the dotted line triangle in the above image. This gives us \[ \|\vec{p}_1 - \vec{p}\|_2 = 2\sin(\frac{\pi}{6} - \theta), \quad \|\vec{q} - \vec{p}_1\|_2 = 2\sin(\theta) \] Putting it all together, we can write our distance metric on the random vector $\mathbf{\vec{q}}$ as \[ D_h(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}}) = \frac{8}{3} \sin \Big( \frac{\pi}{6} - \theta \Big) + \frac{4}{\sqrt{3}} \sin(\theta) \\ \] Sampling this distribution gives us a similar shape to distance metric distributions on the square and triangular grid:

What's interesting to note about this distribution is the the best case (minimal) distance is $2/\sqrt{3}$ when $\theta = (2z+1)\pi/6$ for some integer $z$, which is the worst distance on the triangular grid. For both the square and triangular cases, the best case distance was 1 since it was possible to traverse on a straight path from $\vec{p}$ to $\mathbf{\vec{q}}$. The worst case distance is $4/3$, when $\theta = z\pi/3$. As a result, the best case distance on the hexagonal grid is worse than the best case on the square grid but the worst case on the hexagonal grid is better than the worst case on the square grid. It remains to be seen what the average case is. \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb E[D_h(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}})] &= \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} D_h(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}}) ~ dt \\ &= \frac{6}{\pi} \int_{0}^{\pi/6} D_h(\vec{p}, \mathbf{\vec{q}}) ~ dt \\ &= \frac{6}{\pi} \int_{0}^{\pi/6} \frac{8\sin(\frac{\pi}{6} - t)}{3} + \frac{4\sin(t)}{\sqrt{3}} ~ dt\\ &= \frac{4}{\pi} \\ &\approx 1.273 \end{aligned}\] The expected distance on the hexagonal grid is equal to the expected distance on the square grid! This results seems to defy my intuitions. Every intersection on the hexagonal grid has 3 possible paths with an interior angle of $2\pi/3$ between them. Compared to a square grid which has 4 possible paths at every intersection with an interior angle of $\pi/2$. My intuition tells me that by making paths more sparse, the expected distance should increase, but this doesn't seem to always be the case.

Comparison of Distance Metrics

Topologically speaking, we have constructed three metric spaces $(\R^2, D_s(\vec{p}, \vec{q}))$, $(\R^2, D_t(\vec{p}, \vec{q}))$, and $(\R^2, D_h(\vec{p}, \vec{q}))$ by restricting movement in the Euclidean metric space. To summarize all our above results, we can compare these distance metrics as a function of $\theta$.

This completes the evaluation of every regular polygonal tiling in 2d space. There are many more configurations involving multiple regular polygons (the so-called semi-regular tesselations), or even non-polygon grids such as circle-packing that might be worth analyzing at some point. It might also be interesting to compare distance metrics for polytope tilings in higher dimension space. For now, though, I'll leave it here.