Why Does Bagging Increase Sample Variance?

Bagging (bootstrap aggregating) has become a big part of modern machine learning. It's allowed for the viability of random forests, and enabled more advanced techniques like boosting. But for all it's done, bagging is really quite simple.

Say we have a large dataset with which we want to build a predictive model. One issue we might run into is that our model overbiases our training points, meaning it conforms very well to the data, but in doing so overcomplicates the true relationship. As a result of this, our model is very sensitive to small perturbations in the inputs. Can we train our model to be robust?

One solution is bagging. Instead of training a very complicated model once on the same data, we train several much simpler models on random samples of our dataset and average together the models. Interestingly, the average of several simple models can be arbitrarily complex, and so we can hope to model the true relationship in the data without overfitting our model to the training set.

This begs the questions: how do we randomly sample? The instinctive answer (at least for me) is to choose a random fixed-size subset of the data points for each of our models. But this is, as we will see, non-optimal. At this point, we should start defining things more mathematically.

Suppose we have a $n \times m$ data matrix $X$, where each row is a data point $x$ in $\mathbb{R}^m$. This leaves us with $n$ data points. Now, let $S_i$ be a $k \times m$ data matrix where the $k$ rows correspond to $k$ data points we have randomly samples from $X$. the $i$-th random sample of the data points and $f_i$ denote the $i$-th model we're learning where $0 < i \leq k$. Now we can use a selection matrix $\Alpha_{(i)}$ where $\Alpha_{(i)jk} = 1$ if the $j$-th element we select is the $k$-th data point. This provides us with the relation \[\begin{aligned} \Alpha_{(i)}X = S_i \\ \end{aligned}\] There is an issue now: the set of all possible $S_i$ doesn't biject the set of samples since a set of samples is unordered and the rows of $S_i$ are ordered. Instead, we only care about the count of each element. To find this, we simply find the sum over each column of $A_{(i)}$. This suggests that a bijecting set is $V := \{\Alpha^T\mathbf{1} : \Alpha \in \mathcal{A}\}$. where $\mathcal A$ is just the set of all possible selection matrices. Now for $v \in V$, $v_i$ is the number of $x_i$ in our sample.

If our sample is a subset, $v$ is a vector containing only 0s and 1s, since an element is either in the subset or not. Additionally, the sum of components in $v$ is $k$ since we select $k$ elements in our sample. Let $V_{wor} \subset V$ be the subset of all vectors $v$ that satisfy these constraints. \[\begin{aligned} V_{wor} := \{v \in V: v^T\mathbf{1} = k, v_i \in \{0, 1\}\} \\ \end{aligned}\] or only involving our selection matrix as \[\begin{aligned} V_{wor} := \{\Alpha^T\mathbf{1} : \mathbf{1}^T \Alpha \mathbf{1} = k , \mathbf{1}^TAe_i \in \{0, 1\}\} \end{aligned}\] Instead, suppose we select a sample with replacement. Now still we are selecting $k$ elements, but we forgo the requirement that each element can be selected at most once, so our new set $V_{wr}$ is defined as \[\begin{aligned} V_{wr} := \{v \in V: v^T\mathbf{1} = k, v_i \in \{0, 1, \ldots, k\}\} \end{aligned}\] or \[\begin{aligned} V_{wr} := \{\Alpha^T\mathbf{1} : \mathbf{1}^T \Alpha \mathbf{1} = k , \mathbf{1}^TAe_i \in \{0, 1, \ldots, k\}\} \end{aligned}\] Because of the way we defined these sets, the bijection from samples to these vectors in $V_{wor}$ and $V_{wr}$ is in some sense an isometry, since we are preserving $l_1$ distance. For instance, if $||v_1 - v_2||_1 = 2d$, then $S_2$ differs by $d$ data points from $S_1$. It makes sense, then, that variance in $V$ is a measure of variance in $S$, since variance is a measure of the spread of distances between data points.

As a toy example, let's consider the case where $n = 10$ and $k = 4$. Meaning, we're selecting 4 items from a set of 10. The set $V_{wor}$ might contain a vector like \[\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}^T \end{aligned}\] While the set $V_{wr}$ might contain a vector like \[\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 2 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}^T \end{aligned}\] Now, let's find the variance of $V_{wor}$. Let $Z_{wor} \in \mathbb R^{n \times |V_{wor}|}$ be a matrix where every column is an vector in $V_{wor}$. \[\begin{aligned} \Sigma_{wor} = \frac{1}{|V_{wor}| - 1} (Z_{wor} - \mu_{wor}\mathbf 1^T)(Z_{wor} - \mu_{wor}\mathbf 1^T)^T \end{aligned}\] This is the formula for the sample covariance matrix of $Z_{wor}$. We repeat the same for $V_{wr}$ to get \[\begin{aligned} \Sigma_{wr} = \frac{1}{|V_{wr}| - 1} (Z_{wr} - \mu_{wr}\mathbf 1^T)(Z_{wr} - \mu_{wr}\mathbf 1^T)^T \end{aligned}\] If we sample a distribution from $V_{wor}$ and $V_{wr}$, and call these distributions $\mathbf V_{wor}$ and $\mathbf V_{wr}$, we have \[\begin{aligned} \Sigma_{wor} = \mathbb E[(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])^T] \end{aligned}\] But, our isometry from samples to vectors relies on using an $l_1$ distance metric. So what we care to find is \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb E[\|(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])\|_1] \end{aligned}\] Unfortunately, this is a blog article and not a research paper, so we're going to have to make an approximation \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb E[\|(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])\|_1] \approx \mathbb E[\|(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])\|_2] \end{aligned}\] This somewhat works, since \[\begin{aligned} \frac{1}{\sqrt{d}} \|v\|_1 \leq \|v\|_2 \leq \|v\|_1 \end{aligned}\] The left inequality can be proven using Cauchy-Schwarz and the right inequality with some simple algebraic manipulation. Now, \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb E[\|(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])\|_2] &\approx \sqrt{\mathbb E[\|(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])\|^2_2]} \\ &= \sqrt{\mathbb E[(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])^T(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])]} \\ &= \sqrt{\mathbb E[\text{Tr}((\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])^T)]} \end{aligned}\] Here, we use the clever property that $x^Tx = \text{Tr}(x^Tx) = \text{Tr}(xx^T)$. Now, we can use the fact that the trace of a matrix is a linear function so $\mathbb E[\text{Tr}(M)] = \text{Tr}(\mathbb E[M])$ \[\begin{aligned}\mathbb E[\|(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])\|_2] &\approx \sqrt{\mathbb E[\text{Tr}((\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])^T)]} \\ &= \sqrt{\text{Tr}(\mathbb E[((\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])^T)])} \\ &= \sqrt{\text{Tr}(\Sigma_{wor})} \end{aligned}\] I wrote some code up to calculate these values. \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb E[\|(\mathbf V_{wor} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wor}])\|_2] &\approx \sqrt{\text{Tr}(\Sigma_{wor})} = 1.55 \\ \mathbb E[\|(\mathbf V_{wr} - \mathbb E[\mathbf V_{wr}])\|_2] &\approx \sqrt{\text{Tr}(\Sigma_{wr})} = 2.14 \end{aligned}\] The variance appears to be greater when sampling with replacement as opposed to sampling without replacement. Meaning, to increase the variance of our models, we should feed them data sampled with replacement from our original set of data instead of simply selecting a subset.

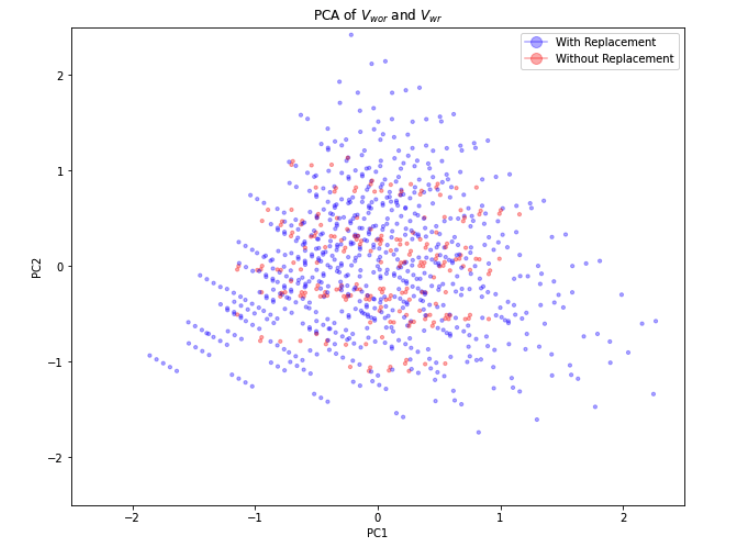

While, we can't visualize the geometry of $V_{wor}$ and $V_{wr}$ due to the vectors being $10$ dimensional, we can use PCA (principal component analysis) to project onto the maximum variance subspace of dimension 2. Here are the results:

It seems like this visualizations supports our claim that drawing with replacement induces more variance.