An "Intuitive" Explanation Behind Optimizing Rayleigh Quotients

Definition: For any \(n \times n\) real symmetric matrix \(M\) and vector \(x \in \mathbb R^n\), the rayleigh quotient is written as $$\frac{x^TMx}{x^Tx}$$ Because both the numerator and denominator are real numbers, the rayleigh transformation for a vector \(x\), \(R_M : \mathbb R^n \to \mathbb R\).

Now why do we care about this seemingly arbitrary equation? To motivate this, let's transform this problem into a simpler one. First, notice that \(R_M\) is scaling invariant, meaning that \(R_M(cx) = R_M(x)\) for all non-zero \(c\): \[\begin{aligned} R_M(cx) &= \frac{(cx)^TM(cx)}{(cx)(cx)} \\ &= \frac{c^2x^TMx}{c^2x^Tx} \\ &= \frac{x^TMx}{x^Tx} \\ &= R_M(x) \end{aligned}\] Since the length of the input doesn't affect the output, we can simply consider all vectors of unit length. In proper notation, we only care about the set of vectors \(\mathcal X = \{x \in \mathbb R^n : ||x||_2 = 1\}\). For any vector \(x \in \mathcal X\), \[\begin{aligned} R_M(x) &= \frac{x^TMx}{||x||_2^2} \\ &= x^TMx \end{aligned}\] because \(||x||_2^2 = 1\).

So what does this tell us? The rayleigh quotient seems to describe a normalized quadratic form, meaning it appears when our model has a quadratic relationship in \(x\) but we don't care about the magnitude of our input.

Of particular interest are two similar problems: what value of \(x\) maximize and minimize \(R_M\). Of course, these problems can be solved by using lagrange multipliers or in the special case where \(M \succeq 0\), using Cholesky decomposition. But neither of these approaches, when I first encountered the Rayleigh quotient, satisfied me with an intuitive explanation of the answer. I'm going to attempt to detail an alternate explanation that relies more on geometry and requires nothing more than eigendecomposition to understand.

First, let \[U = \begin{bmatrix} u_1 & u_2 & \cdots & u_n \end{bmatrix}\] where \(u_i\) is the eigenvector corresponding to the \(i\)-th largest eigenvalue of \(M\). Then, because there are \(n\) eigenvalues and all eigenvalues are orthogonal to one another, \(\text{rank}(U) = n\), meaning we can express \(x = Uz\) for some \(z \in \mathbb R^n\). Intuitively, we are representing \(x\) as a linear combination of the eigenvalues of \(M\) with weights \(z\). Substituting this representation into \(R_M\), \[R_M(Uz) = \frac{z^TU^TMUz}{z^TU^TUz}\] For any orthonormal matrix \(U\), \(U^TU = I\), (this isn't too hard to show), so we can rewrite the above equation as \[\begin{aligned} R_M(Uz) &= \frac{z^TU^TMU^Tz}{z^Tz} \\ &= R_{U^TMU}(z) \end{aligned}\] Now, using eigendecomposition we can diagonalize any real symmetric matrix into a matrix \(U\) with columns spanning the orthonormal eigenbasis of the matrix and a diagonal \(\Lambda\) containing the eigenvalues. So \(M = U\Lambda U^T\) and we now have \[\begin{aligned} R_{U^TMU}(z) &= \frac{z^TU^TU\Lambda U^TUz}{z^Tz} \\ &= \frac{z^T\Lambda z}{z^Tz}\\ &= R_{\Lambda}(z) \end{aligned}\] Putting it all together, we have shown that \[ R_M(x) = R_\Lambda(z) \] Meaning, importantly that \[\max_x R_M(x) = \max_z R_\Lambda(z)\] and \[\min_x R_M(x) = \min_z R_\Lambda(z)\] We begin by focusing on the maximum case. From earlier we showed that \(R_\Lambda\) is scaling invariant, so considering only the unit ball \[\begin{aligned} \max_z R_\Lambda(z) &= \max_{||z||_2 = 1} R_\Lambda(z) \\ &= \max_{||z||_2 = 1} z^T\Lambda z \end{aligned}\] Now, since \(\Lambda\) is diagonal, this product can easily be expanded \[\begin{aligned} \max_{||z||_2 = 1} z^T\Lambda z &= \max_{||z||_2 = 1} \begin{bmatrix} z_1 & \cdots & z_n \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \lambda_1 & & \\ & \ddots & \\ & & \lambda_n \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} z_1 \\ \vdots \\ z_n \end{bmatrix} \\ &= \max_{||z||_2 = 1} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \lambda_i z_i^2 \end{aligned}\] Here \(\lambda_i\) represents the \(i\)-th largest eigenvalue. Now you can make a greedy exchange argument that the optimal solution is one where \(z_1 = 1\) and all other \(z_i = 0\), stating that if you were to deviate from this solution, then the objective value would always decrease.

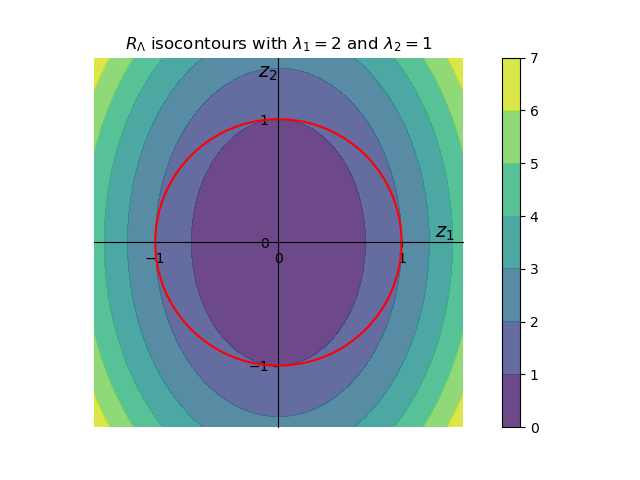

This works fine, but I want to try giving a geometric interpretation for this. Consider for simplicity the 2 dimensional case where \(\lambda_1 > \lambda_2 \)

If we plot the constraint \(||z||_1 = 1\) we'll obtain a circle of radius 1 around the origin. Our maximum point must reside on border of this circle. Our function \(R_\Lambda\) has the shape of a paraboloid but we can visualize this function in 2d with the help of isocontours

The isocontours form axis-aligned ellipses. Looking at the values of \(R_\Lambda\) on the red circle, it is clear that the largest value is at \(z = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \) and the smallest value occurs at at \(z = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} \), corresponding to a maximum value of \(\lambda_1 = 2\) and a minimal value of \(\lambda_2 = 1\) respectively.

This seems hand wavy, but it can be shown that an axis-aligned ellipsoid inscribed within a hypersphere only touches the sphere at the edge of its longest axis. This corresponds to the minimal value of \(R_\Lambda\). Likewise, the axis-aligned ellipsoid that circumscribes a hypersphere on touches the sphere at the end of its shortest axis. This corresponds to the maximal value of \(R_\Lambda\). On the above figure, inscribed and circumscribed ellipsoids correspond to the dark purple and the light purple ellipsoids respectively.

Now, since the value of \(z\) that maximizes \(R_\Lambda(z)\) is \[z_{max} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ \vdots \end{bmatrix}\] we can recover what value of \(x\) maximizes \(R_M(x)\) \[\begin{aligned} x_{max} &= Uz_{max} \\ &= u_1 \end{aligned}\] And the maximal value of \(R_M(x)\) is \[\begin{aligned} \max_{x} R_M(x) &= R_M(u_1) \\ &= \frac{u_1^TMu_1}{u_1^Tu_1} \\ &= \lambda_1 \frac{u_1^Tu_1}{u_1^Tu_1} \\ &= \lambda_1 \end{aligned}\] Likewise, the value of \(z\) that minimizes \(R_\Lambda(z)\) is \[z_{min} = \begin{bmatrix} \vdots \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}\] Giving us the minimal value of \(R_M(x)\): \[\begin{aligned} \min_{x} R_M(x) &= R_M(Uz_{min}) \\ &= R_M(u_n) \\ &= \frac{u_n^TMu_n}{u_n^Tu_n} \\ &= \lambda_n \frac{u_n^Tu_n}{u_n^Tu_n} \\ &= \lambda_n \end{aligned}\] In essence, what we have done is shown that because the rayleigh quotient is scaling invariant, we can represent the vector \(x\) as a linear combination of eigenvectors for \(M\) with weights on the unit ball. This means that the output of the rayleigh quotient is a linear combination of the eigenvalues of \(M\) where each weight is between 0 and 1 and the weights sum to 1. This is a convex hull, meaning the minimum and maximum must occur at eigenvalues.